It's all about face for Obama in Asia

In English, it's "face". In Korean, it's chae myun. And, for those of us who work in China, we know it as mianzi.

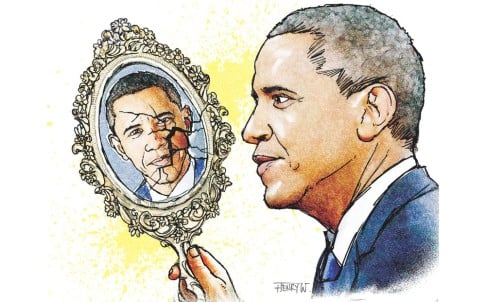

US President Barack Obama's cancellation of a planned trip to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation forum's summit in Indonesia and the East Asia Summit in Brunei got me thinking about diplomacy and the Chinese concept of "face".

Contrast Obama's shrinking and now cancelled return trip to Asia with President Xi Jinping's ongoing first trip to Southeast Asia since taking office in March. With great fanfare, Xi, not Obama - who spent part of his childhood in Indonesia - became the first foreign leader to address Indonesia's parliament.

That's some serious "face time" for Xi.

If the US can be outmanoeuvred by Russia, what about by an increasingly assertive China?

Should Obama have made it back this week to Indonesia and Brunei, as well as to Malaysia and the Philippines, he would have been welcomed with the appropriate respect and ceremony that Asian hospitality and diplomatic protocol would dictate for any American head of state.

Yet, the view from Asia of recent American leadership is not necessarily a positive one. That does not bode well for the so-called pivot, or rebalance in US policy, towards Asia.

This is, after all, a region where there remains tremendous respect for not just thoughtful but also strong and decisive leaders. Singapore's senior statesman Lee Kuan Yew, who as prime minister took his nation from third world to first world in a few decades and who just celebrated his 90th birthday, is a leading example.

Ironically, as foreign businesspeople continue to take steps to understand China's shifting landscape and the implications of recent leadership changes in what is now the world's second-largest economy, Obama has provided an unfortunate "teaching moment" about what is arguably, along with money and power, one of the three great motivators in modern China. That is the concept of "face".

In Chinese, as in English, the definition of face includes that space between a person's forehead and chin -- one's eyes, nose and mouth. But as Scott D. Seligman, a historian, former Fortune 500 business executive and author ofChinese Business Etiquette explains, for Chinese and many others in Asia, face also describes a somewhat intangible concept that is tied to notions of personal dignity and respect.

Losing face in Asia can have a lot more consequence than a bit of momentary embarrassment. Credibility erodes, and power, prestige, influence and even expectations of your abilities can decline.

Just more than a year ago, Obama drew his line in the sand for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

"We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilised," Obama said. "That would change my calculus. That would change my equation."

So what happened? Chemical weapons were used. A non-response would have been a huge loss of face for the US president. But as the American public and numerous members of the US Congress made clear, the president failed to make a strong enough case for the US to enter into another military action so soon after Libya, Iraq and Afghanistan.

And so, the president did an about-face on whether he needed to have Congress authorise what seemed to be a potential strike of ever-shrinking size. That was before he welcomed a decision to delay a possible vote. All of this may well have been seen by Obama and his defenders as a face-saving way out of a dilemma of his own making, but the view from Asia was of a leader who was far from decisive.

Make no mistake though. Russian President Vladimir Putin was not practising the Chinese concept of "giving face" - described by Seligman as "enhancing someone else's esteem through compliments, flattery or a show of respect" - when Russia shrewdly stepped into the breach by taking advantage of a seemingly offhand comment by US Secretary of State John Kerry as the basis for a proposed agreement that would avert an American military strike. Putin has helped keep Assad in power in the near term and reasserted Russian influence in the Middle East.

If the US can be outmanoeuvred by Russia when it comes to Syria, what about by an increasingly assertive China in Southeast and East Asia? As much of the region comes to terms with China's economic and military growth, a US that moves beyond budget impasses and issues of face, and complements defence and diplomacy with greater commercial, educational and cultural engagement would be welcome in Asia. A "soft power" pivot if you will.

Why will a Chinese manager stick stubbornly to an announced policy, even when subsequent events prove it to have been irretrievably misguided, when a Western boss would have long since reversed himself? The answer, Seligman says, is the concept of face. And in the case of Obama and Syria, we may well have the worst of East and West - stubborn insistence by Obama that he does have a consistent, thought-through policy when the world sees otherwise.

Seligman writes that "no one can say how much money has been wasted, how many people toppled from power or how many friendships have been destroyed" over the abstract concept of face. But as those of us who live in Asia know, and the people of Syria may ultimately find out, face can also be a deadly serious business.

Obama might yet again change his mind on Syria, congressional positions may evolve on budgets, and regime change might come once again to the Middle East. The flow of history towards greater economic and individual freedom may be slow and uneven, but it is inevitable, whether Myanmar today, or Syria or North Korea tomorrow. Budget crisis or not, there is no loss of face in holding fast to that belief, whether or not Obama shows up any time soon in Asia. --

Curtis S. Chin served as US ambassador to the Asian Development Bank under presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, and is managing director of advisory firm RiverPeak Group, LLC

No comments:

Post a Comment