Sunday, October 13, 2013

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Online Video in China

China’s online-video market is the largest and most innovative in the world. It is also the most competitive

The Chinese stream

LATER this month PPTV, a Chinese online-video firm, will release a new reality show called “The Goddess Office” (pictured) about four young women living together in a house, trying to create their own e-commerce company. Viewers will be able to ask the stars questions and send them money and ideas for their start-up. The show will employ familiar television elements: the comedic rapport of the characters in “Friends” and the commercial ambitions of contestants in “The Apprentice”. But this “television” show will run exclusively online, rather than on a traditional TV network.

Around the world online video is becoming a bigger and more sophisticated business, but nowhere is that truer than in China. The country has the largest number of online-video viewers: around 450m, or nearly 80% of the internet-connected population. Their numbers will rise to around 700m by 2016, according to iResearch, which tracks the industry. In America and Europe, online video has yet to supplant broadcast- and pay-TV, but in China it seems rapidly to have done so. A government news source has said that in 2012 only 30% of households in Beijing watched TV, down from 70% three years earlier—although official figures are not always reliable.

Google’s YouTube video service is blocked in China, but local companies, including Youku Tudou and Sohu, are wildly popular (see table). There is lots of user-generated content, but viewers spend most of their time watching professional shows, such as the full-length films, television dramas and comedies that the websites license from China and around the world. Media gluttons can devour all this content without charge, as long as they sit through the advertisements.

Online-video sites in China owe much of their popularity to the government’s tight regulation of the TV industry: all of the 3,000-plus stations are state-owned and their programmes are heavily censored. Rules about content range from the predictable (no shows inciting political unrest) to the puzzling (no depictions of time travel). It takes months for programmes to get official approval for broadcasting, and only an estimated 30% of shows that are made get aired on TV.

Online-video sites, in contrast, need a government licence to operate, but are left to police the content on their sites themselves—perhaps because the government never expected them to attract such a mass of viewers. “In principle it’s the same, but in reality it’s very difficult to say what the standards are for the online-video content players,” says Victor Tao, the boss of PPTV. For example, last month the government ordered television channels to edit episodes of “Pleasant Goat and the Big Big Wolf”, a long-running children’s cartoon, because it was deemed to be too violent. But online-video firms that host episodes of the show seem not to have been given the same instruction.

Around five years ago Chinese online-video firms started competing directly with television by making their own programmes, and this year they will spend a combined 1 billion yuan ($164m) on shows like “The Goddess Office”, according to Jiong Shao of Macquarie Securities, an advisory firm. (The same thing is happening in America, too: three internet firms, Netflix, Amazon and Hulu, have been making their own programmes, to cut the cost of licensing content and to create a more tempting offering for subscribers.)

Online-video shows resonate more with the people aged between 15 and 40, who flock to their sites. For example, “Surprise”, a series made by Youku that parodies such things as university entrance exams, has been viewed 260m times since it premiered on Youku in August.

This year the number of people watching online video on their mobile devices has surged. Analysts expect the arrival of fourth-generation mobile networks to accelerate this trend. People who watch shows on mobile devices spend more time viewing, overall, than those on desktop PCs, according to Victor Koo, the boss of Youku. The main challenge for him and his rivals is to lure more advertisers.

The size and innovation of the Chinese online-video industry may be unique, but its economics are not. Like all online-video companies that rely on ad revenues, Chinese firms find it hard to make much money, if any. Although the industry had revenues of around 9 billion yuan in China last year, few firms are profitable. This is because their costs are so high. Buying bandwidth to deliver content to so many users is expensive, and so are the rights to license content. As a result there have been nearly as many mergers as there are elimination rounds on “The Voice of China”, one of China’s most popular TV shows. Last year Youku and Tudou, the most popular online-video sites, merged. In May Baidu, an internet-search giant, bought PPS, a video site, for $370m and merged it with its existing video service, iQiyi.

Self-interest has helped change the treatment of copyright in China. Several online-video firms are stockmarket-listed, and as a result they take content licences seriously, especially since as makers of their own shows they now have intellectual property to protect. They are suing those who pirate their content and are thus stealing some of their potential traffic. Youku alone has several hundred copyright lawsuits on the go.

Turning the channel

Online-video firms are also setting their sights on the living room. Several firms are designing internet-enabled set-top boxes; LeTV is making an internet-enabled television. By invading TV stations’ home turf they can make themselves more valuable to advertisers—and may even be able to start charging subscription fees.

However, there is no guarantee that this will make the industry profitable. “The biggest enemy to the online-video service providers is consumer behaviour,” says Mason Xu of Heyi Capital, a venture-capital firm. Because the government runs the television “business”, consumers are used to paying little for cable—the equivalent of around $3 a month for digital cable. So it is unclear if they will pay much for online video, even if it comes with extra benefits such as ad-skipping. A study by McKinsey, a consultancy, suggests that around 15% of Chinese viewers might subscribe to online video on an internet-enabled TV set if it cost no more than 30 yuan ($5) a month. But even that is probably optimistic.

Getting slaughtered in the ratings by online video has prompted China’s TV channels to try harder. A wave of singing competitions and dating shows—some of them adaptations of successful Western ones—have come on air in recent years, particularly on provincial satellite channels. Meanwhile CCTV, the central government’s giant channel, continues to lose viewers. Last month officials scolded other stations for their “vulgar” and “excessive” entertainment and pushed for more “morality-building” and educational shows. Some singing contests are being forced off the air, and from next year satellite stations will be limited to one foreign show a year.

This will only accelerate the broadcasters’ decline and the switch to online viewing. “TV is useless now,” one person posted on a Chinese weibo, or microblogging site. “Fortunately we still have computers.” -- The Economist - 2013 November 9

Monday, October 7, 2013

Face

In English, it's "face". In Korean, it's chae myun. And, for those of us who work in China, we know it as mianzi.

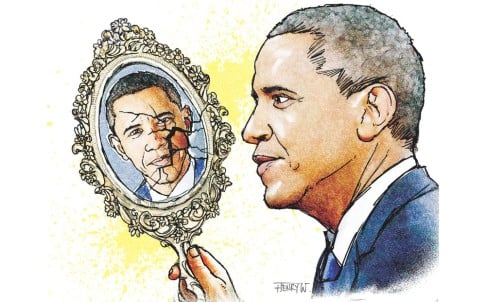

US President Barack Obama's cancellation of a planned trip to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation forum's summit in Indonesia and the East Asia Summit in Brunei got me thinking about diplomacy and the Chinese concept of "face".

Contrast Obama's shrinking and now cancelled return trip to Asia with President Xi Jinping's ongoing first trip to Southeast Asia since taking office in March. With great fanfare, Xi, not Obama - who spent part of his childhood in Indonesia - became the first foreign leader to address Indonesia's parliament.

That's some serious "face time" for Xi.

If the US can be outmanoeuvred by Russia, what about by an increasingly assertive China?

Should Obama have made it back this week to Indonesia and Brunei, as well as to Malaysia and the Philippines, he would have been welcomed with the appropriate respect and ceremony that Asian hospitality and diplomatic protocol would dictate for any American head of state.

Yet, the view from Asia of recent American leadership is not necessarily a positive one. That does not bode well for the so-called pivot, or rebalance in US policy, towards Asia.

This is, after all, a region where there remains tremendous respect for not just thoughtful but also strong and decisive leaders. Singapore's senior statesman Lee Kuan Yew, who as prime minister took his nation from third world to first world in a few decades and who just celebrated his 90th birthday, is a leading example.

Ironically, as foreign businesspeople continue to take steps to understand China's shifting landscape and the implications of recent leadership changes in what is now the world's second-largest economy, Obama has provided an unfortunate "teaching moment" about what is arguably, along with money and power, one of the three great motivators in modern China. That is the concept of "face".

In Chinese, as in English, the definition of face includes that space between a person's forehead and chin -- one's eyes, nose and mouth. But as Scott D. Seligman, a historian, former Fortune 500 business executive and author ofChinese Business Etiquette explains, for Chinese and many others in Asia, face also describes a somewhat intangible concept that is tied to notions of personal dignity and respect.

Losing face in Asia can have a lot more consequence than a bit of momentary embarrassment. Credibility erodes, and power, prestige, influence and even expectations of your abilities can decline.

Just more than a year ago, Obama drew his line in the sand for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

"We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilised," Obama said. "That would change my calculus. That would change my equation."

So what happened? Chemical weapons were used. A non-response would have been a huge loss of face for the US president. But as the American public and numerous members of the US Congress made clear, the president failed to make a strong enough case for the US to enter into another military action so soon after Libya, Iraq and Afghanistan.

And so, the president did an about-face on whether he needed to have Congress authorise what seemed to be a potential strike of ever-shrinking size. That was before he welcomed a decision to delay a possible vote. All of this may well have been seen by Obama and his defenders as a face-saving way out of a dilemma of his own making, but the view from Asia was of a leader who was far from decisive.

Make no mistake though. Russian President Vladimir Putin was not practising the Chinese concept of "giving face" - described by Seligman as "enhancing someone else's esteem through compliments, flattery or a show of respect" - when Russia shrewdly stepped into the breach by taking advantage of a seemingly offhand comment by US Secretary of State John Kerry as the basis for a proposed agreement that would avert an American military strike. Putin has helped keep Assad in power in the near term and reasserted Russian influence in the Middle East.

If the US can be outmanoeuvred by Russia when it comes to Syria, what about by an increasingly assertive China in Southeast and East Asia? As much of the region comes to terms with China's economic and military growth, a US that moves beyond budget impasses and issues of face, and complements defence and diplomacy with greater commercial, educational and cultural engagement would be welcome in Asia. A "soft power" pivot if you will.

Why will a Chinese manager stick stubbornly to an announced policy, even when subsequent events prove it to have been irretrievably misguided, when a Western boss would have long since reversed himself? The answer, Seligman says, is the concept of face. And in the case of Obama and Syria, we may well have the worst of East and West - stubborn insistence by Obama that he does have a consistent, thought-through policy when the world sees otherwise.

Seligman writes that "no one can say how much money has been wasted, how many people toppled from power or how many friendships have been destroyed" over the abstract concept of face. But as those of us who live in Asia know, and the people of Syria may ultimately find out, face can also be a deadly serious business.

Obama might yet again change his mind on Syria, congressional positions may evolve on budgets, and regime change might come once again to the Middle East. The flow of history towards greater economic and individual freedom may be slow and uneven, but it is inevitable, whether Myanmar today, or Syria or North Korea tomorrow. Budget crisis or not, there is no loss of face in holding fast to that belief, whether or not Obama shows up any time soon in Asia. --

Curtis S. Chin served as US ambassador to the Asian Development Bank under presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, and is managing director of advisory firm RiverPeak Group, LLC

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)